the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The Russian settlements on Spitsbergen – history, current socio-economic status and challenges for the future development

Barbara Schennerlein

Spitsbergen is distinct compared with other Arctic archipelagos, especially regarding its the political and socio-economic status. Despite the Spitsbergen Treaty1, which was signed 100 years ago, the territory is commonly perceived as part of Norway. All the more, the Russian settlements have a particular position on Spitsbergen. The article is introduced by a short historical review, drawing attention also to the different opinions related to the discovery history. In the following, this paper strives to present a deeper dive into the current socio-economic status of today's Russian community on Spitsbergen. The analysis was created from questionnaires worked out by the inhabitants of the two Russian settlements Barentsburg and Pyramiden as well as from interviews with executives of different sectors. Derived from this, factors which could influence the upcoming development of the settlements were formulated.

Spitzbergen unterscheidet sich von anderen arktischen Inselgruppen insbesondere was den politischen und sozio-ökonomischen Status betrifft. Trotz des Spitzbergenvertrages, der vor hundert Jahren unterzeichnet wurde, wird das Territorium allgemein als Teil Norwegens wahrgenommen. Umso mehr haben die russischen Siedlungen auf Spitzbergen eine spezifische Stellung. Der Beitrag leitet ein mit einem kurzen historischen Rückblick, in dem auch die unterschiedlichen Ansichten zur Entdeckungsgeschichte angesprochen werden. Im Folgenden soll ein tieferer Einblick gegeben werden in den derzeitigen sozio-ökonomischen Status des heutigen russischen Gemeinwesens auf Spitzbergen. Die Analyse wurde auf der Basis von Fragebögen erstellt, die Einwohner der zwei russischen Siedlungen Barentsburg und Pyramiden erarbeitet haben als auch mit Hilfe von Interviews, die mit Führungskräften verschiedener Bereiche geführt wurden. Davon abgeleitet, werden Faktoren formuliert, die die kommende Entwicklung der Siedlungen beeinflussen können.

- Article

(7516 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Due to its geographical location, extending from 74 to 81∘ N, Spitsbergen belongs to the northernmost inhabited areas in the world. However, the archipelago, which is covered by glaciers by two-thirds, has never been settled by the indigenous population. In spite of this, currently such settlements such as Longyearbyen, Barentsburg and Ny-Ålesund have infrastructure that could be compared to Middle European standards. However, these are not ordinary settlements: even though they are permanently inhabited, nobody spends their entire life there. According to the current regulations there is not a single person who was both born and buried on Spitsbergen.

Spitsbergen officially appeared on world maps after Willem Barents' third expedition in an attempt to find the Northeast Passage in 1596–1597. The name of the archipelago, which is commonly used today, was given by its discoverer. The story of Barents' expedition is widely known and accepted. Nevertheless, it is disputable up to the present day which country the actual discovery should be attributed to – the Netherlands, Norway, England or Russia. The arguments provided by the English side used to refer to Hugh Willoughby's expedition, who set sail on the Bona Esperanza as captain of the fleet with two other vessels in 1553 to find a sea route to China. What can be considered certain today is that the land he discovered and described rather imprecisely was Novaya Zemlya (Asher, 1860; Hayes, 2003).

Norway often refers to the mention of Svalbard in the Icelandic Annals of the second half of the 16th century (Islandske Annaler indtil). It is stated that in 1194 “Svalbardi fundinn”: Svalbard was discovered (Hantschel, 1964). However, this extremely briefly described geographic discovery made without any further explanations could never be clarified completely. Which island was in fact meant in this entry – Northeast Greenland? Jan Mayen? Even Franz Josef Land was taken into consideration in different theories.

Russian sources repeatedly quote the letter by the German humanist and geographer Hieronymus Münzer addressed to King John II of Portugal from 14 July 1493 (Obruchev, 1964), in which he proposes organizing a westward voyage to reach China. This letter, which was compiled by the physician Hartmann Schedel from Nuremberg, mentions the Grand Duke of Moscow and the discovery of a gigantic island of Grulanda, with a coastline of 300 miles (483 km) length, populated by a large settlement under his rule (Grauert, 1908). The Pomors had hunted on the archipelago for many centuries and were the first regular winterers here (Wiese, 1935). The Grumanlanen, as they were called in their native land, when they went hunting on the archipelago Grumant, apparently Greenland (on early maps also called Gruntland, Engroneland), had a lot of experience with coastal exploration in the Arctic Ocean. According to the Soviet archeological excavations since the end of the 1970s, between the 16th and 18th centuries it was possible to find Russian settlements almost on the entire archipelago (Starkov, 1998). Some of these results are represented in the Barentsburg Pomor Museum. The oldest artifacts date back to the year 1548 due to laboratory studies (Starkov, 1998).

The history of the archipelago discovery has not been completely clear until now. The main question is whether, and if so when, people were on Spitsbergen before Barents' expedition, and, above all, which country the discovery can attributed to. Arlov (2005) considers this question from different perspectives and comes to the following conclusion: “It would appear that national sentiments remain an influence that cannot be ignored.” This becomes obvious when visiting two museums on Spitsbergen. The historical exhibition in the Barentsburg Pomor Museum reports about the Pomors' ways from the coasts of the White Sea to the north and to Scandinavia. In addition, it documents the excavations on Spitsbergen with objects from the 16th century (Fig. 1). On the other hand, in Svalbard Museum on one of the boards one can read the following:

Russian hunting in Svalbard began early in the 18th century … . English and Dutch businessmen had traded in the White Sea from the end of the 16th century. We believe that they gave the Russian merchants in Archangel knowledge of whaling near Svalbard.

Figure 1Objects of the 16th century found during an excavation of a Russian house in the region of Stabbelva river (west coast of Nordenskiöld Land), presented in the Barentsburg Pomor Museum (photo: B. Schennerlein).

Even though for centuries Spitsbergen remained a so-called “no man's land”, by no means did it mean that in this high-latitude area there were no political discussions about the use of this land.

Initially the claim of the Danish Kingdom was recognized, as for a long time the prevailing opinion was that the landmass was a western part of Greenland; the first confrontation started with the beginning of the first economic activities in the whaling period. In the 17th century these were, in particular, the English and the Dutch, but also the Spaniards and the Danes who competed for the rich yields on Spitsbergen. The division of the territory into allocated fishing zones enabled them ultimately to resolve the disputes, which at times were fought with armed vessels (Hantschel, 1964).

After the whales were almost completely exterminated, the economic importance of Spitsbergen declined for most nations. Only Russian Pomors continued hunting on the archipelago. The next phase of economic exploitation of resources started with the extensive coal mining activities since the end of the 19th century. This time was characterized by a number of activities – at first without any consequences – to clarify the status of Spitsbergen, starting with a Swedish initiative in 1870–1871. Subsequently, the USA, the UK, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden, Norway and Denmark were involved. There were two main camps to differentiate: those who wanted to put Spitsbergen under the full sovereignty of a state and others who wanted to maintain the status quo: terra nullius (Hantschel, 1964). With the permanent settlement of miners and the connected conflicts, it became urgently necessary to create regulations. After numerous preliminary conferences, bilateral agreements and the interruption of the process by World War I, the Spitsbergen Treaty was finally signed in 1920. It has been signed by more than 50 states to date. In Norwegian parlance, the archipelago is now called Svalbard. The key points of the 10 articles of the treaty (Treaty concerning Spitsbergen, 1920) include the following:

-

Full and absolute sovereignty of Norway over the archipelago of Spitsbergen is recognized, under the conditions set out in the following articles.

-

All citizens and all companies of every nation under the treaty are guaranteed to have free access to ports and their territorial waters.

-

Everyone has the right to fish or undertake any kind of trade, mining or industrial activity without impediment.

-

Norway is responsible for the preservation of flora and fauna and, if necessary, can take appropriate measures.

-

Spitsbergen remains demilitarized.

The expedition of the Arctic explorer Vladimir Rusanov (1875–1913?) in 1912 marked the beginning of the Russian mining activities on Spitsbergen. He secured a number of coalfields for Russia in the area that would later become Grumant and the little harbor Colesbay. In 1913 Russian emigrants established the company Grumant A. G. Agafeloff & Co, which in return founded the mining settlement Grumant. In 1920 the Anglo Russian Grumant Company Ltd. was established with the goal of operating the mine in Grumant. The economic development of the Northeast Passage caused an increased demand for coal, beginning in the 1920s. At that time, Russian ships sailing east from Murmansk or Archangelsk used as a rule coal from Donbass – a disadvantage due to the large distance from the northern ports. Apart from that, with the country's rapid industrialization, these coal reserves were required for major industrial projects in the country. Spitsbergen became the most important source for the ports in the western sector of the Northeast Passage (Armstrong, 1952). In 1931 the Soviet company Sojusljesprom started operation in Grumant, a successor to the Grumant A. G. Agafeloff & Co. In the same year, with a decree of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union, Trust Arktikugol was established, and all the property rights for the exploration of the acquired land and all rights and obligations of the Soviet Union on Spitsbergen were transferred to it (Arktikugol, 2020). In 1932 the Soviet company took over the mine in Grumant, as did the mine in the Barentsburg area previously operated by the Dutch company Nespico. In 1961 Grumant was closed due to unprofitable mining conditions, including the difficult conditions endured to export coal from the mine. In the 30 years of its existence, the mine produced over 2 million metric tons of coal (Arktikugol, 2020).

The company Arktikugol took over the land rights at Pyramiden already in 1927 from Sweden. The active development of the area started only after World War II. Before its closure in 1998, it was the world's northernmost coal mine.

Among the nations which signed the Spitsbergen Treaty, only Norway and Russia are still conducting economic activities on Spitsbergen today. Both countries subsidize their coal mining industry. Coal mining in Ny-Ålesund, Norway, was finally stopped after a serious mine accident in 1963, and Sveagruva was closed in 2016. Today the mine in Longyearbyen produces coal only for the needs of the place. The coal mining industry in Barentsburg guarantees supply for the town itself and exports to Europe. Over the past few years, in addition to coal mining, there has been a significant shift to other economic sectors, including tourism and research.

The situation that exists on this northern archipelago today is unique in the world: the areas of one state – Russia – exist on the sovereign territory of another state – Norway, mutually influenced by their own state sovereign regulations, but, on the other hand, limited by a contract that has remained unchanged for a hundred years. During this time, the whole century was marked by the devastation from World War II and, subsequently, from global economic and social upheavals. Both countries are currently regarded to belong to opposing political camps. According to the perception in Central Europe, Spitsbergen is a part of Norway. Russia on Spitsbergen is perceived, if at all, only from two perspectives. Political headlines such as “Norway and Russia: Battle over the Arctic Ocean”, “Spitsbergen divides Norway and Russia” and “Russian Power Games on Spitsbergen” report about the archipelago. And for the few tourists who reach Barentsburg or the abandoned settlement Pyramiden, their stay is connected with a picturesque experience, a journey into the Russian past.

This article intends to attempt to take a look behind the mostly media-generated image. What influence have the processes of the past had on the Russian settlements? How is the life organized for their residents today? And what development opportunities does the Russian community have in the future?

Much of the work was done during Arctic Floating University 2019, a multidisciplinary international research and educational expedition project, organized by the Northern Arctic Federal University Arkhangelsk and the Russian Federal Service for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring. Offshore and onshore research was carried out by six groups aboard research vessel Professor Molchanov.

Currently, Barentsburg is the only “living” Russian place. Located in a terraced shape on the shore of Grønfjorden, it has a complete infrastructure system to remain self-sufficient: power station, school and kindergarten, wastewater treatment plant, hospital, supply facilities, harbor facilities, culture center and gym (Fig. 2).

Only a few remains of the old houses are left from Grumant. Pyramiden, located on the Billefjord about 120 km away from Barentsburg, is a place “frozen in time”. All buildings still exist – swimming pool, dining room, mechanical workshops – but nobody uses them or lives in the well-preserved apartment blocks (Fig. 3). There is only one hotel, which is operated temporarily for tourist purposes. Around 1000 people lived and worked here at peak times.

I would say that in the Soviet times Barentsburg and Pyramiden were the closest to communism. The principle of communism was implemented here: from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs. The food was free, i.e., one could eat in a canteen for free. I mean there were some luxuries for money, but the rest was free … there was a farm here; there were cows, goats, pigs – we had our own meat. There were greenhouses in Pyramiden, it was virtually possible to grow bananas. The swimming pool, again – very important, with sea water, very healthy. [...] And the paradox is that communism was built on the Norwegian territory. (Gushchin, 2019).

In the 1990s there was a start of the recession process, which finally led to the decision in 1998 to stop the coal mining industry in Pyramiden. People gave up everything and had to rush out of the place: “it was like Chernobyl, a ghost town. Looters immediately began to rob it [...] they even took the piano and loaded it onto the yacht in Pyramiden from some house. Everything was stolen.” (Gushchin, 2019).

Figure 3A part of the settlement of Pyramiden, in the background the Nordenskiöld glacier (photo: B. Schennerlein).

Since 2008, only after the decisions made by the government commission for Spitsbergen the development has regained positive momentum – the reconstruction of the place began.

In contrast to Norwegian coal settlements, all Russian settlements had been inhabited by families since their foundation. In 1932, five children overwintered in Barentsburg; in the following year there were already 22 children, and in 1934 there were 45 children between the ages of 2 months and 14 years (Stavnitser, 1948). In the 1990s, Spitsbergen was predominantly populated by Russians from Barentsburg and Pyramiden (1990: 2407 Russian, 1125 Norwegian residents) (Statistics Norway, 2020). Today, Barentsburg still has around 450 inhabitants. The Russian territories are represented by the consulate general located in the town.

Below, insight is provided into the current economic and social situation in the Russian settlements. For this purpose, during a two-time stay in 2019, some interviews were conducted and questionnaires were distributed to the residents. The interviewees were representatives who had a comprehensive view of the economic, social and political situation. These were as follows:

-

consul general of the consulate general in Barentsburg on Spitsbergen;

-

the head of the Arctic Travel Company Grumant, part of Trust Arktikugol, which has been responsible for all essential issues in the Russian settlements since it was founded;

-

a miner (participant 18 out of 28 respondents) who has been working in the coal mine in Barentsburg since the Soviet era and, therefore, was able to assess the changes which occurred over the past decades very well.

The interviews are available in transcribed written form in Russian language. The original Russian citations were translated into English for use in this paper.

The questionnaire was filled out by 28 people, which amounts to 6 % of the current population. Besides statistical information, the questionnaire included four large areas.

Questions about the economic situation

-

significance of Russian coal production at different times/for different locations/for different objectives;

-

tasks of Trust Arktikugol;

-

economic development in the main areas of coal mining/tourism/research – today and in the future;

-

factors that have an influence on the situation in Barentsburg;

-

cooperation with the Norwegian settlements;

-

future viability of the place.

Questions about general living conditions

For this purpose, the Arctic Social Indicators were used, a project of the Nordic cooperation, which is aimed at researching and tracking of the changes in human development in the Arctic (Larsen et al., 2010, 2014). These indicators have been adapted for the purpose of this study and concern the following areas:

-

municipal administration;

-

satisfaction with material living conditions/educational opportunities/cultural environment/health care.

Questions about tourism

-

special features of offers in the tourism industry;

-

strategy for tourism development;

-

target groups/statistical information;

-

cooperation between Norwegian and Russian travel agencies.

Questions about science and research

-

importance of scientific research in Barentsburg for Russia;

-

cooperation with research institutions in and outside Spitsbergen.

The results of the study refer mainly to Barentsburg with its coal mining industry, developing tourism and the important Kola Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Some of the people operating in the tourism industry work both in Barentsburg and in Pyramiden.

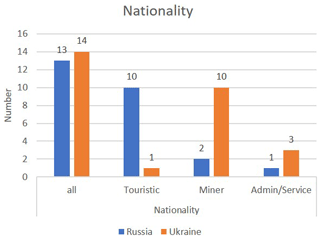

In total, 20 of the respondents were male, and 8 were female. The average age of the respondents was 35 (male: 38; female: 30). The nationality of all 28 respondents was distributed almost equally across Ukraine and Russia (Fig. 4). What is striking in this context is the division into professions. While the tourism industry is almost completely occupied by Russians (including guides, managers, bartenders, catering workers), the situation with around 280 miners is exactly the opposite (and such professional groups as electrical engineers, locksmiths, power plant workers). The presence of Ukrainians in the coal mines has a long tradition. At the beginning of the 1930s the vast majority of the miners came from Donbass (Stavnitser, 1936). The respondents in the administration/service sectors are the embassy personnel or sales staff and cooks.

2.1 Economic situation

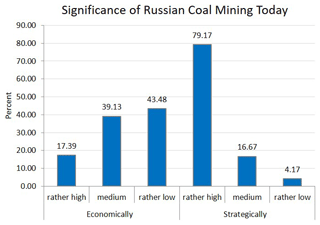

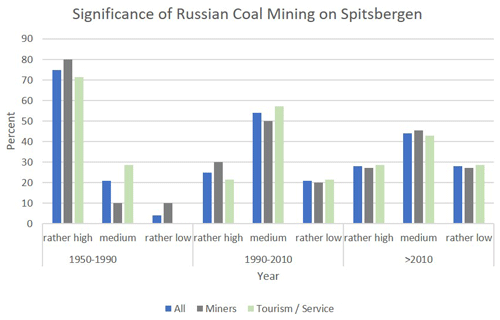

Regarding the questions about Russian coal production in different time periods (Fig. 5), it was recognized across all professional groups that its importance has been steadily decreasing since the post-war years (describing the situation in 1950–1990 75 % of the respondents said it was “rather high”; regarding the years 1990–2010 the answer “rather high” was given by only 25 % of the respondents; as far as the current situation is concerned, the answer was given by 28 % of the respondents). It is interesting to note that in relation to the current time there is no significant difference between employees in tourism/service and the mining industry. This difference, however, can still be seen in the past, when miners, as expected, assess the importance of mining noticeably higher (“rather high”: 1950–1990 – 80 %/1990–2010 – 30 % versus 71 %/21 % of those employed in tourism).

Figure 5Significance of Russian coal mining on Spitsbergen in different time periods and from the perspective of different job groups.

Looking at the information regarding the purpose of using coal (Fig. 6), one can make a very clear statement: coal production does not have any economic weight; the vast majority of the respondents (almost 80 %) put emphasis on the strategic importance. It could also be seen in the statements of Trust Arktikugol, which defines a production plan of approximately 120 000 t a year based on the remaining coal reserves. This is intended to ensure the operation of the mine until 2024 (Arktikugol, 2020). A total of 30 000 t is used for the power plant in Barentsburg, and 90 000 t is exported to Europe. Around 40 years ago, an average of 250 000 t was mined per year and up to 450 000 t at peak times. However, today, production is no longer profitable – which also concerns the Norwegian mine – the subsidies amount to around 50 % (Rogozhin, 2019).

In the mid-term, it is expected that together with a further reduction in Norwegian coal production, the efforts to invest in renewable sources of energy and the expansion of natural conservation areas, corresponding requirements will be also imposed on the Russian mines. Thus, the request of Trust Arktikugol to take over the Svea mine, which was closed by Norway, was rejected since the area was designated as a nature reserve immediately after its closure (Gushchin, 2019).

At this point there is a conflict with the Spitsbergen Treaty: on the one hand, everyone is free to conduct their economic activities on Spitsbergen; on the other hand, Norway has to take care of the nature protection. In order to protect nature, helicopter flights are also very restrictively permitted by the Norwegian side. Russian workers performing transport flights between Longyearbyen and Barentsburg were granted a special permit, but only if these are directly related to the operation of the mine. Transportation of scientists or tourists is prohibited. Arguments that it would also serve the economic purposes are not accepted (Gushchin, 2019). However, helicopter flights are now also restricted for other tourist agencies (Rogozhin, 2019). The issue is, therefore, very important for the Russian settlements, as they depend on Longyearbyen in terms of transport logistics. The airport is located there, and Barentsburg can only be reached from Longyearbyen by ship in summer or by snowmobile in winter.

With the realization that, on the one hand, coal reserves are running out, but, on the other hand, in order to protect the environment, emissions have to be reduced, both Norway and Russia are confronted with this issue and develop corresponding strategies. A noticeable change in the infrastructure can already be seen today in Longyearbyen, where there is a variety of tourist offers, the UNIS (University Centre in Svalbard) as well as Ny-Ålesund, which was developed for international polar research beginning in 1968. In the Russian settlements this process started only in the last decade. Since 2013, the strategy for developing tourism has been intensively implemented parallel to coal mining. For instance, the Arctic Travel Company Grumant, which belongs to Trust Arktikugol, offers tours that cannot be found at other agencies on Spitsbergen, such as visiting an active coal mine, which is a worldwide unique opportunity.

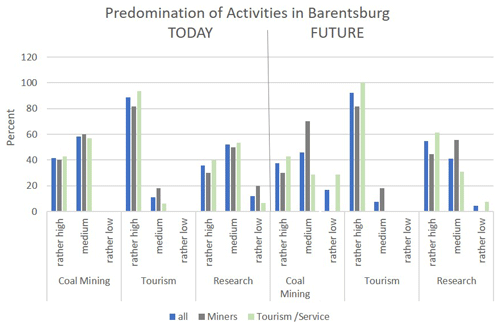

What do the residents think of the move towards tourism? The outstanding message in Fig. 7 represents the importance that tourism is already accorded today, by all profession groups (“rather high”: 88.9 % of all respondents; 81.8 % of miners; 93.8 % of employees in tourism sector). These figures are about twice as high as the importance of coal production (“rather high” 41.7 % of all respondents; 40 % of miners; 42.7 % of employees in tourism sector). As far as the future development is concerned, the difference will be even larger – only 30 % of miners estimate the importance of coal mining as rather high; however, this figure amounts to 42.9 % in the tourism industry. It should be noted that the miners rate their own work both now and in the future as less important compared to those who do not work in the mining industry.

In the future, tourism will become more important (92.3 % of all respondents; the same 81.8 % of miners; but 100 % of employees in the tourism sector). This positive dynamic could also be noticed in discussions with the residents: in recent years the development of the place was distinctively financed by tourism.

In 2018, Spitsbergen was visited by around 70 000–80 000 tourists. Around 36 000 of them visited the Russian settlements; however, only 600–700 people were from Russia. Norwegian tourists make up around 65 %–72 % (Rogozhin, 2019).

The reason for such a small number of Russian tourists is twofold. First of all, Russian tourists are more focused on southern countries; the other reason is economic. Although the Arctic Travel Company Grumant offers the same tours on Spitsbergen at significantly lower prices compared with Norwegian agencies, these tours in the Arctic are still expensive regarding the average income in Russia. Apart from that, there is no culture of traveling to the Arctic; very little is known about these areas – this applies, however, to other countries as well. Nevertheless, the few Russians who come to the Arctic stay significantly longer (on average 5–8 d) and, therefore, generate about 20 %–25 % of the total turnover in tourism (2018: EUR 2.4 million) (Rogozhin, 2019). Other tourists are often brought to Russian settlements via Norwegian tour operators or are passengers on cruise ships and usually spend a few hours in Barentsburg or Pyramiden for a short sightseeing tour. The tours here are conducted by Russian tour guides. The doubled number of Russian tourists is expected in the following years; however, the process should be generally moderate – the goal is not to have a large number of tourists but to attract those tourists who want to stay longer and to familiarize themselves with history and nature. There are different strategies for the two Russian locations: Barentsburg is seen

as a modern Russian village in the Arctic, where tourists can learn a lot of different stories because Barentsburg and its surroundings are the intersection points of different nationalities, absolutely different activities in different periods of time. The Americans began to coal mine here … Barentsburg itself was founded by the Dutch. Now it is a Russian village, where a lot of Ukrainians live and work. Near the village there is Finniset Cape, where there was the last whaling factory on Spitsbergen, a place where whales were caught. Next to it, there was the first radio station on Spitsbergen; Pomors lived also here … There are a lot of nationalities here as well as famous people. Nansen was here, Rusanov was here. (Rogozhin, 2019).

For Pyramiden, a place which was abandoned in 1998, a different path was chosen:

Pyramiden, on the other hand, is a time machine, it is a monument to the history of the exploration of the Arctic in the era of socialism. We want to leave Pyramiden as it was in the period of 1950–1980s. As an example that socialism existed … Perhaps in 10 years we will decide to take a completely different strategy for positioning of Pyramiden. But in the near future, we would like to maintain Pyramiden as a monument, because, on the one hand, we keep an interesting past, on the other hand, this interesting past gives us opportunity to develop tourism, as we earn a lot of money there. (Rogozhin, 2019).

In recent years, the Kola Scientific Center's research station in Barentsburg has been greatly expanded. The regular shipping traffic between Murmansk and the Russian settlements, which started in 1933, required reliable weather and ice conditions forecasts (Wiese, 1935). Therefore, a polar station was first founded in Grumant in 1931, which was relocated to Barentsburg in 1933. In that year, the station was a part of the research program within the Second International Polar Year (Romanenko et al., 2019). The residents of Barentsburg are rather indifferent regarding the importance of the research (Fig. 7). The response “rather high” increases from 36 % to 54.5 %, but the evaluation of the corresponding part of the questionnaire shows that there is rather little knowledge about this area. Between 56 % and 75 % of the respondents stated that they knew nothing about the research results of the Kola Scientific Center polar station in Barentsburg or about economic or strategic importance of the research. Almost none of the respondents knows whether there are collaborations with other research stations on Spitsbergen, in Russia or worldwide (87 % to 100 %).

2.2 Social life

Barentsburg is a city which was founded to mine coal, the same way as Longyearbyen, Grumant and Pyramiden. Therefore, it is not surprising that a company – Trust Arktikugol – has been responsible for all the needs of the place besides the actual mining industry, such as supply, housing construction and administration, infrastructure development, transport system, education and health care. A similar situation can be observed in Longyearbyen (Store Norske Kulkompani), in Ny-Ålesund with Kings Bay Company, and in Kiruna, Sweden, with the mining company LKAB. In recent years, Longyearbyen has seen a local democratization process due to diversification of the working process. Since 2002, there has been a community council that has a say in local issues. As far as can be seen from the questionnaires and interviews, the comprehensive responsibility of Trust Arktikugol is hardly questioned.

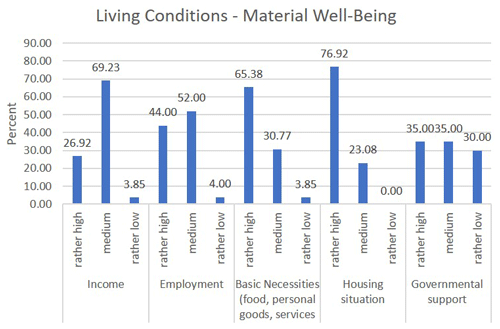

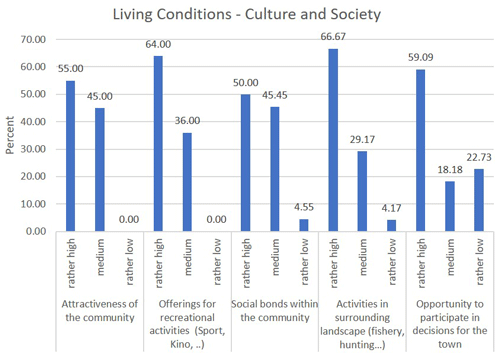

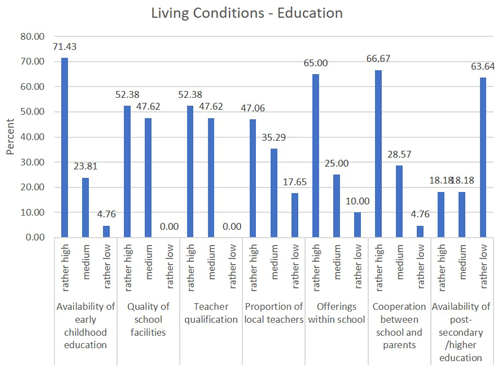

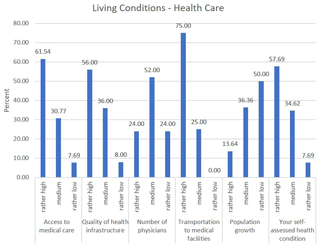

The analysis of the social situation comprised four focal points: satisfaction with material living conditions (Fig. 8), satisfaction with cultural and social life (Fig. 9), satisfaction with available educational offers (Fig. 10) and satisfaction with health care (Fig. 11).

One of the factors which received the lowest approval ratings is salary for the employees (Fig. 8). If only miners are taken into account, it is possible to state that only 18.2 % of the respondents are satisfied with their salary (72.7 % medium). Although the payment is fairly poor (between RUB 40 000 and 60 000), miners from the war zones in Donbass keep coming here because it is peaceful and they have a secure income for their families (Gushchin, 2019). The satisfaction with salary for tourism employees is somewhat higher (36.4 % rather high). However, due to daily contact with Norwegian tour guides they have comparison with Norwegian salary structures. Thus, it becomes more common for employees to switch to Norwegian agencies.

Most of the respondents are satisfied with the provision (rather high: more than 65 %). In particular, today, people value the possibility of being able to buy fresh fruit and vegetables in contrast to the past, when almost exclusively canned goods were available (Miner, 2019). Most people (almost 77 %) are satisfied with the living conditions. The townscape is dominated by two multi-story colored apartment blocks, in which small but modern apartments can be used by miners and their families: great progress compared to the living conditions at the end of 1980s. At that time, two workers used to share a small room with a sink; when they had to work different shifts, the life process became very hard (Miner, 2019). Today, the town is equipped with internet connection, mobile communication and digital television. Even the abandoned settlement Pyramiden can now be reached via mobile phones (which, by the way, is not something everyone approves of). It is reported how a letter transport by ship could still take 6 months during the Soviet era (Miner, 2019). In general, government support for the development of the location is seen as in need of improvement (30 % rather poor).

Satisfaction with cultural and social life is consistently high (Fig. 9). What should be particularly emphasized is the work of the various music and dance groups of the local cultural center, which perform regularly for both residents and guests. People can also enjoy a wide range of sport activities. All respondents are aware of or even take part in regular cultural exchange programs or sports competitions with the residents of Longyearbyen. It is a central part of residents' everyday life that has a long tradition.

Already in the 1930s, the opera Rusalka was performed in the town's cultural center with its own scenery. The residents of Longyearbyen also took part in some performances (Stavnitser, 1948). This exchange exists at the local political level as well. The consul general emphasized that their cooperation with the governor of Spitsbergen has always been based on mutual trust, no matter which consul represented Russia on Spitsbergen. However, some issues cannot be solved by the governor; they must be solved in Oslo. Apart from cultural and sports exchange between the residents of Barentsburg and Longyearbyen, there are common official protocol events. For example, the governor takes part in the celebrations on 9 May and 12 June in Barentsburg dedicated to Victory Day and Russia Day, respectively. There is also a common wreath-laying ceremony at the monument to commemorate the fallen Norwegian soldiers during World War II.

Approximately every 2 months there are working meetings between the Russian and Norwegian sides, the governor of Spitsbergen, Trust Arktikugol, the Consul General of Russia on Spitsbergen, at which all problems are openly discussed and – as far as it is within his power – can be solved by the governor (Gushchin, 2019).

While 59 % agree that participation opportunities in local issues are relatively high, almost 23 % of those questioned say that the opportunities for participation are insufficient. This indicator is one of the highest in the category “rather low”.

There is a large building in Barentsburg, also recognizable by the beautiful exterior design, which houses a kindergarten and school (Fig. 10).

Most of the respondents are satisfied with the offers for about 60 children in the town (Fig. 11), which in particular concerns pre-school education, additional offers of the school for children, and the cooperation between teachers and parents (all positions are rated with “rather high” – between 65 % and 71 %). What is especially noticeable is that there is lack of further-education opportunities for young people (64 % “rather low”) – children have to go back to the mainland.

One of the modern buildings in Barentsburg is the local hospital. This is where the entire basic medical care for the location takes place – all in all, the respondents are satisfied with it (Fig. 12). With regard to the quality of the infrastructure (44 % “medium” and “rather low”) and the number of doctors (total 76 % “medium” and “rather low”), there is still development potential. One of the questions asked in this area concerned the population growth in the town: half of the respondents recognized this as insufficient (“rather low”). In this context, the report on the times at the beginning of the 1990s can be mentioned, when Barentsburg had more than 3 times as many inhabitants.

It was a completely different time. First of all, a lot of polar explorers lived here, somewhere around 1500 people. They worked somehow, everyone liked it, people were young and healthy […] It was a little bit easier to work, it was easier to work, because so many people worked, and the work was in full swing (Miner, 2019).

All in all, 50 % of those surveyed stated that they were very satisfied with the changes in Barentsburg in the past 5 years, 40 % were satisfied, and only 10 % rated their satisfaction with the changes as “rather low”. The improvement of the living conditions and the renovation of the housing stock were always mentioned as positive changes. Among other positive changes the respondents also mentioned the improvement of the road conditions, the fact that Pyramiden was revived, more tourists visiting the place (and, as a result, more events), positive impact of tourism on the attractiveness of the place, the improvement of the infrastructure and the food supply, and the opening of a new restaurant and cafe.

What predictions about the Russian settlements on Spitsbergen can now be made based on the previous development processes? With regard to future development, the residents themselves should first have their say. When asked about their expectations for the future, the respondents mentioned some specific requests: conversion of the power plant to renewable energy sources, the approval of the development plan for Barentsburg, increased funding of the cultural center, but also the improved supply and further development of tourism, further development of coal deposits, providing jobs and high salaries, the improvement of social relationships, and the desire to have personal experiences with life in the Arctic. Some people answered they liked the place the way it is. They would like to have peace and harmony and want to see Barentsburg as a modern place, with fewer old buildings and full of tourists. They want to be satisfied with their work and their lives.

On the basis of the available questionnaires, transcribed interviews and research on geopolitical activities, especially of Norway and Russia in relation to Spitsbergen, some factors can be named that can influence the life of the Russian settlements in the future.

Geopolitical factors. Due to the special legal status of Spitsbergen, geopolitical issues are as important for the settlements as local decisions. The direction in which Norwegian Arctic policy will develop in the future will play an important role. The same way as Russia, Norway clearly defines its presence on Spitsbergen as a strategically important goal (Svalbard, 2016). In the past, the fairly open wording of the articles in the Spitsbergen Treaty has repeatedly led to differences in their interpretation. In general, there is a tendency towards the implementation of the law in the interests of Norway (Grydehøj et al., 2012). An example of this is the establishment of a fishery protection zone in 1977, which de facto corresponds to an exclusive economic zone of 200 nautical miles in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The fact whether Norway is entitled to do so and who is allowed to fish in this area is assessed not only by Russia but also by countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain and Iceland in a completely different way as Norway. Recently, as a similar case, courts started to deal with the catching of snow crab off the coast of Spitsbergen. The EU is also involved in this dispute (Doyle et al., 2019). Norway clearly attests their rights based on the Spitsbergen Treaty (Svalbard, 2016). So far, the conflicts have largely been resolved through bilateral agreements. In the past, there were further points of friction regarding the interpretation of the demilitarized status of Spitsbergen. Besides that, since 2014, geopolitical activities are often influenced by the conflict with Ukraine. The Consul General of Russia on Spitsbergen who worked at the Russian Embassy in Oslo in 2010–2015 reports that before 2014 there were very close relations between Norway and Russia, also in the military area. There was collaboration between the two countries in the area of naval forces exercises, and there was a plan to hold ground forces maneuvers together with Norway. At conferences with the participation of other NATO member states, there was often a question asked regarding the key to such a successful cooperation. Today, the situation has changed completely; there is great mistrust at the central political level (Gushchin, 2019).

Another area of conflict arises from the way taxes paid by Trust Arktikugol are used. According to the Spitsbergen Treaty, taxes and duties levied on Spitsbergen may only be used to develop the settlement structure on Spitsbergen. Arktikugol initially pays the taxes to the Norwegian state, which then determines for which purposes the money will be used. If a large part is then invested into the development of the Longyearbyen Airport, this could lead to disagreements about the interpretation of the Spitsbergen Treaty (Gushchin, 2019).

However, a possible solution regarding environmental fund for Spitsbergen, a Norwegian foundation, has been found. Applications for projects can be submitted twice a year; Trust Arktikugol has already received NOK 1.5 million for reconstruction work. Currently, funds are being requested for the reconstruction of the port facilities in Pyramiden, and the Russian side is optimistic that funds will be made available for the renovation of further buildings in Pyramiden (Gushchin, 2019).

Essentially, it is estimated that only the stabilization of the relationship between the USA and Russia will result in an improvement of the relationship between Norway and Russia, and in this case, it will be possible to resolve conflict areas with regard to Spitsbergen (Gushchin, 2019).

So far, the Russian side has repeatedly complained that proposals for negotiations and diplomatic correspondence are not supported (Grønning, 2018).

Russia is usually perceived as an opponent of Norway when it comes to dealing with conflicts, but “Russia's role in the archipelago is one that suits the interests of many other signatory states, which in a sense depend on Russia's resistance to Norwegian sovereignty in order to retain their own rights. […] These signatories are willing to leave the fighting of such battles to Russia so they need not get their own diplomatic hands dirty.” (Grydehøj et al., 2012).

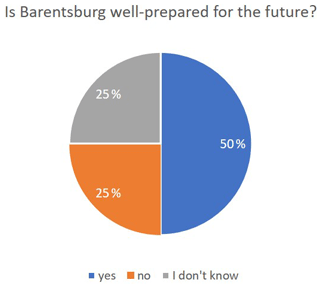

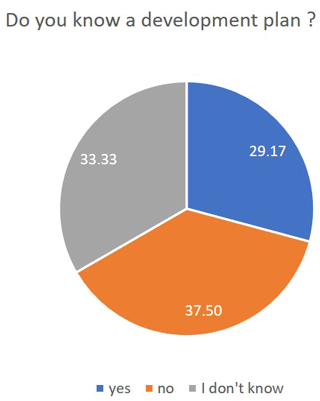

Economic and socio-political factors. In addition to the global political factors, which play a greater role in local development than elsewhere due to the special status of Spitsbergen, other circumstances that influence the future of Russian settlements can also be named. An important point seems to be the perception by the Russian authorities. There has been quite a positive development of Barentsburg recently, and half of those surveyed stated that the place was well prepared for the future (Fig. 13). However, more than 70 % of the respondents do not know anything about the development plan for the town (Fig. 14).

There is a strategy plan regarding the Russian presence on Spitsbergen with goals for 2012–2020. The key points include the development of the Barentsburg social infrastructure and the development of Pyramiden. Many goals have been achieved (Gushchin, 2019). The development of the strategy until 2032 started about 5 years ago. However, due to a number of changes taking place at the moment, it is currently being revised and is expected to contain specifications by 2040 (Rogozhin, 2019). Various institutions including the Russian Embassy in Oslo, the consulate general in Barentsburg, Trust Arktikugol, the AARI, the ministry of energy and others have been asked to provide input for the new strategy. It is going to be developed by the government commission for the Russian presence on Spitsbergen, led by Deputy Prime Minister Yury Trutnev, who is also responsible for the work of the State Commission for Arctic Development (Gushchin, 2019). However, at the time of the interviews, none of the input providers knew whether and to what extent the work would be taken into account at all. A more regular interaction between those affected and those responsible for decision-making could, on the one hand, have a positive impact on the strategy to be developed, and it could also increase understanding and identification with it.

However, it was clearly expressed that coal will still be mined in 5 to 10 years, not because it is needed, but because the miners form the backbone of the society in Barentsburg (Rogozhin, 2019). The question of coal extraction and, therefore, the presence of miners – mostly from Donbass – is one of the essential ones for the direction in which Barentsburg will develop. Provided that possible demands from the Norwegian side to reduce coal production can be negotiated, similar to the conflict of fishery rights around Spitsbergen (as long as Norway is producing coal, Russia will do the same), there is also the question of development in eastern Ukraine. In the event that peaceful conditions are restored and comparable work opportunities are available, a large proportion of the miners would leave Spitsbergen to return home (Miner, 2019). Then the following question will be raised: what makes this place exceptional? The second pillar which is being developed – tourism – will not be a complete substitute. A place – only for and with tourists? It would be the second Pyramiden, a museum site. A lively city needs permanent, committed residents.

The questionnaires provide information regarding the direction in which life in the Russian settlements on Spitsbergen should develop. The residents answer as follows:

-

Better payment for miners is a strong incentive to work in the Arctic.

-

More participation in the decision-making process regarding the development of the place increases identification with the living environment.

-

More government support for the projects is seen by the residents as a priority.

-

There need to be offers for further education and high school in the town. Longyearbyen has demonstrated this, especially with the establishment of the UNIS.

-

A closer cooperation with the research station “Barentsburg” – apart from its research function – could also make a contribution to new educational opportunities. Today, the work of the research station appears to be a completely separate part of the life of Barentsburg.

-

Measures to increase the population again are also closely related to the offer of new educational opportunities.

-

Tourism is an opportunity for the Russian settlements – not only economically. However, it cannot exist without the mine. In the meantime, the balance between coal production and tourism has been successfully achieved, and the earnings are reinvested into the development that benefit the location, so both industries can benefit from each other (Rogozhin, 2019). Discussions with the government have now dispelled earlier intentions of using tourism earnings in favor of subsidized mining (Rogozhin, 2019).

The further development in this direction will make the places more international. New ideas, offers and job opportunities will emerge, not only for Russian and Ukrainian citizens. This way, Barentsburg (and partly Pyramiden) will initially only catch up with what has already been achieved in terms of education, tourism and social investment in the Norwegian settlements. However, the Russian settlements can also use other potential that derives from many years of their diverse experience on Spitsbergen. The key can be found in the Spitsbergen Treaty itself: the model of Russian settlements on the Norwegian territory as a blueprint for international normality on the archipelago in the future. What is meant by that? Russia is – as mentioned before – the only foreign economically active nation on the Norwegian territory today. Nevertheless, the Spitsbergen Treaty allows all signatory states to have equal rights to access the archipelago and to conduct their economic activities there. In this respect, Russia is only a real example of possible future scenarios. In the scientific field, the growing number of research stations in Ny-Ålesund shows that interest in the Arctic and especially in Spitsbergen is increasing. The growing economic interest in the Northeast Passage due to climate change is well known. Non-Arctic neighbor states such as South Korea and China operate research stations in Ny-Ålesund and participate in Russian expeditions to Spitsbergen (such as the AFU expedition in 2019 mentioned above). Research is not an end in itself, as it will be followed by further activities, including economic ones, which have to be negotiated with Norway based on the framework of the Spitsbergen Treaty, i.e., also with the other signatory states. Russia, and, above all, its local representatives, can make a contribution as a consultant and mediator in the further internationalization of the archipelago due to their many years of experience on Spitsbergen in politics as well as practical matters, thus promoting the spirit of the Spitsbergen Treaty for the 21st century.

After having the status of terra nullius for centuries, in the past 100 years Spitsbergen has been shaped by the Spitsbergen Treaty politically and legally and mainly by coal mining economically. The two active nations on the archipelago, Norway and Russia, have since been linked to their settlements in a kind of cooperative rivalry. The inhabitants of the Russian settlements have lived through different systems during this time – socialism peak with all the privileges for those working in the Arctic, decline in the 1990s and realignment in the past 10 years. Although the local situation has always been shaped by the “big politics”, it has been possible to maintain a close and trusting relationship with the Norwegian neighbors at a local level and to resolve controversial issues over the years. It would be desirable for the trust and close cooperation that works so well between the local bodies to serve as an example of cooperation at the central level.

In particular, the changes in the social and cultural area of the past 5 to 10 years described above are largely viewed as positive by the residents of Barentsburg. Especially the strong focus on tourism in both settlements, which according to those responsible is profitable, has been widely accepted. It aims at opening up new economic sources, but at the same time it has a noticeably positive effect on the local social climate, as the surveys show. The effort to change Barentsburg and to establish it as a modern Russian place with comfortable living conditions and to preserve its rich history is clearly recognizable. It remains to be seen whether this exclusive focus (in addition to the unprofitable coal mining) will support the future. The expectations of the residents result in concrete possible fields of action for the future, such as the creation of financial incentives, educational offers and participation opportunities.

Turning the view from the inside of the situation in the Russian settlements to the outside, the experiences of the local institutions in the way of repeatedly renegotiating the existence of Spitsbergen within the framework of the Spitsbergen Treaty can be groundbreaking and helpful for future activities of other signatory states in the archipelago.

Data collection was carried out by means of questionnaires (paper-and-pencil method due to the circumstances – miners during work breaks) and electronically recorded interviews. For evaluation purposes, the questionnaires were subsequently recorded electronically. The data are not publicly available and can be requested from the author if necessary.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

I am extremely grateful to the Arctic Center for Strategic Studies of the Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M. V. Lomonosov for the support of my work on Spitsbergen. Special thanks are due to Alexander Saburov, who arranged the interview contacts and provided other support. I would also like to thank all the residents of Barentsburg with whom I was able to speak for their openness and the opportunity to gain insight into their lives today. I would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments.

This paper was edited by Bernhard Diekmann.

Arktikugol: https://www.arcticugol.ru/, last access: 26 February 2020.

Arlov, T. B.: The Discovery and Early Exploitation of Svalbard. Some Historiographical Notes, Acta Boreal., 22, 3–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830510020343, 2005.

Armstrong, T.: The Northern Sea Route – Soviet Exploitation of the North East Passage, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 79–88, 1952.

Asher, G. M.: Henry Hudson the navigator. The original documents in which his career is recorded. Collected, partly translated, and annotated with an introduction, Hakluyt Society, London, 1860.

Doyle, A. and Fouche, G.: Abide by the claw: Norway's Arctic snow crab ruling boosts claim to oil, Reuters, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-norway-eu-snowcrab/abide-by-the-claw-norways-arctic-snow-crab-ruling-boosts-claim-to-oil-idUSKCN1Q3115, last access: 14 February 2019.

Grauert, H.: Die Entdeckung eines Verstorbenen – Zur Geschichte der großen Länderentdeckungen, in: Historisches Jahrbuch XXIX. Jahrgang, edited by: Weiß, J., Kommissions-Verlag von Herder & Co., München, 304–334, 1908.

Grønning, R.: Op-Ed: Need debate on the Svalbard Treaty, High North News, available at: https://www.highnorthnews.com/nb/op-ed-need-debate-svalbard-treaty (last access: 26 February 2020), 10 November 2017/update: 24 October 2018.

Grydehøj, A., Grydehøj, A., and Ackrén, M.: The Globalization of the Arctic: Negotiating Sovereignty and Building Communities in Svalbard, Norway, Isl. Stud. J., 7, 99–118, 2012.

Gushchin, S.: Consul General, Consulate General of the Russian Federation at Spitsbergen, Personal interview, Barentsburg, 30 June 2019.

Hantschel, A.: Weltgeschehen am Rande des Polarmeeres – Spitzbergen in der Weltpolitik, Marienburg-Verlag, Würzburg, 205 pp., 1964.

Hayes, D.: Historical atlas of the Arctic, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, 2003.

Larsen, J. N., Schweitzer, P., and Fondahl, G. (Eds.): Arctic Social Indicators – a follow-up to the Arctic Human Development Report, Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, 2010.

Larsen, J. N., Schweitzer, P., and Petrov, A. (Eds.): Arctic Social Indicators ASI II: Implementation, Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, https://doi.org/10.6027/TN2014-568, 2014.

Miner, S.: Employee at the State Trust Arktikugol, Personal interview, Barentsburg, 10 September 2019.

Obruchev, S. V.: Russkiye pomory na Shpitsbergene v XV veke i chto napisal o nikh v 1493 g. nyurnbergskiy vrach [Russian pomors on Svalbard in the 15th century and what a Nuremberg doctor wrote about them in 1493], Izdatel'stvo “Nauka”, Moskva, 1964 (in Russian).

Rogozhin, T.: Head Arctic Travel Company “Grumant”, State Trust Arctikugol, Personal interview, Barentsburg, 4 July 2019.

Romanenko, F. and Ezhova, N.: Pervyye meteorologi sovetskogo Shpitsbergena [The first meteorologists of Soviet Svalbard], Russkiy vestnik, 40, 22–23, available at: https://www.arcticugol.ru/index.php/novosti/novosti-kompanii/281-russkij-vestnik-shpitsbergena-2-40-2019 (last access: 15 May 2019), 2019 (in Russian).

Starkov, V. F.: Ocherki istorii osvoyeniya arktiki [Review of the Arctic pioneering], Vol. I Spitsbergen, Scientific World, Moskva, 1–96, 1998 (in Russian).

Statistics Norway: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/07430/, last access: 27 February 2020.

Stavnitser, M.: Russkiye na Shpitsbergene [Russians on Spitsbergen], Izdatel'stvo Glavsevmorputi, Moskva, 111–125, 1948 (in Russian).

Stavnitser, M. E.: Barentsburg, Sovyetskaya Arktika, Glavsyevmorput', Moskva, No. 2, 55–66, 1936 (in Russian).

Svalbard: Report to the Storting (white paper) – Meld. St. 32, Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security Svalbard, 1–119, available at: https://publikasjoner.dep.no/ (last access: 19 March 2019), 2015–2016.

Treaty concerning Spitsbergen 2020: http://www.verfassungen.eu/n/spitzbergenvertrag1920.htm, last access: 4 April 2020.

Wiese, V. Y.: Istoriya issledovaniya Sovetskoy Arktiki [History of exploration of the Soviet Arctic], Sewkraigis, Archangelsk, 1935 (in Russian).

This is related to the archipelago of Spitsbergen as formulated in article 1 of the treaty. Today, often the Norwegian term Svalbard is used to avoid confusion related to the western island of Spitsbergen and the archipelago of Spitsbergen. In Russian, the term Spitsbergen is commonly used for the archipelago.