the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Wilhelm Filchner – hierarchy and insufficient leadership on the Second German Antarctic Expedition

The Second German Antarctic Expedition (1911–1912) did not have a good start, because Wilhelm Filchner (1877–1957) failed to secure his position as expedition leader. His problems began long before the expedition set sail: he had the support neither of the scientists and officers on board nor of the scientific community in Germany. The enforced choice of the captain, who suffered from syphilis, brought the expedition to the brink of collapsing. In addition, the rivalry between the groups on board the Deutschland, and the usual challenging circumstances any expedition confronts in these regions, led to mutiny at the end of their time in Grytviken, South Georgia. Upon the expedition's return to Germany, “courts of honour” took place to adjudicate on the mutual accusations. This article reviews some of the reasons why this expedition was disaster-prone. The article is based on research from my PhD thesis (Rack, 2010).

Die zweite Deutsche Antarktis-Expedition (1911–1912) stand unter keinem guten Stern. Wilhelm Filchner (1877–1957) konnte seine Position als Expeditionsleiter von Anfang an nicht behaupten. Manche Probleme begannen schon lange bevor die Expedition auslaufen konnte. Er hatte nicht den Rückhalt der Wissenschaftler die mit ihm am Schiff waren und auch nicht derer, die in der Polarforschung der Zeit involviert waren. Die auferzwungene Wahl seines Kapitäns, der sich im Endstatium von Syphilis befand, machte die Expedition zu einer Gradwanderung. Die rivalisierienden Gruppierungen innerhalb der Expeditionsteilnehmer und die Probleme, die fast jedes Unternehmen in diesen Gegenden zu bestehen hatten, führte letztendlich zu einer meutereiähnlichen Auseindersetzung in Grytviken, Südgeorgien. Zurück in der Heimat wurden Ehrengerichte angestrengt, um die gegenseitigen Anschuldigungen zu einem Ende zu bringen. Diese Abhandlung zeigt einzelne Missstände auf, die diese Expedition zum Scheitern verurteilte. Dem vorliegenden Artikel liegen einige Kapitel meiner Dissertation zugrunde (Rack, 2010).

- Article

(871 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Wilhelm Filchner wanted to establish Germany in the ranks of the great foreign Antarctic explorations with a German Antarctic expedition. When he announced his proposal at the Berlin Geographical Society in Berlin (Gesellschaft für Erdkunde Berlin), 5 March 1910, some in the scientific community in Germany were not confident about his chances of success and did not fully support this event. Erich von Drygalski (1865–1949), expedition leader of the German National Antarctic Expedition (1901–1903), also known as the Gauss expedition, was one of his harshest critics. However, some influential members in the science community and military ranks advocated his plans. Albrecht Penck (1858–1945) was one of them. Filchner partially developed his expedition programme based on Penck's theories about glaciation during the ice ages. The Association of the German Antarctic Expedition (Verein Deutsche Antarktische Expedition) was influential in the recruitment of the expedition members and controlled the expedition's finances. Most of the scientists and officers were under the impression that the expedition was a marine endeavour to display the greatness of the German Navy, but Filchner and a handful of scientists had only a science expedition in mind. This was a fundamental point of conflict from the start. The enforced choice of the captain was another critical issue because he was not only a driving force in the group opposed to Filchner that formed on the journey south, but he was also critically ill and his decisions were heavily influenced by his medical conditions. Filchner, who had problems working with peers, hindering his attempts at leadership, exacerbated the situation. This became evident before the expedition started and was aggravated during the expedition, exposing the underlying flaws and personal sensitivities of those involved. This article, based on the research in my PhD thesis (Rack, 2010), demonstrates how weak leadership compromised a potentially successful expedition, and the subsequent series of conflicts resulted in an expedition marred by a collapse in structural and interpersonal relations.

Filchner presented his expedition plans to scientists and the wider public, showing that his ambition was to establish the German Empire in the ranks of Antarctic exploration. The expedition promised great scientific findings, and Filchner himself had a talent for getting many influential people on board when it came to funding, especially the support of the Bavarian King Luitpold, who introduced a lottery that encouraged other donations from different sources. The Association of the German Antarctic Expedition was founded to oversee the finances and other formal decisions. Filchner welcomed this arrangement at first, but he allowed the association to take control of crucial decision-making such as the recruitment of the expedition members. He, effectively, lost control in the preparation period and, in particular, the choice of the captain – a position that is crucial for the success of any expedition.

Filchner had planned to recruit a Norwegian captain when he purchased the ship Deutschland in Norway (Krause, 2012). However, the ship sailed under the flag of the German Empire and the decision was made by the committee of the Association of the German Antarctic Expedition to recruit a German captain; Richard Vahsel was their choice. He had Antarctic experience as fourth officer on the first German National Antarctic Expedition. Drygalski expressed his favour for Vahsel in a letter to Hofrat Hermann Wagner (1840–1929): “I hope and expect that Vahsel holds on to the matter” and further in the conversation he stated the following: “Big sledging trips are not to expect but scientifically lots can happen if Vahsel keeps the upper hand.” (von Drygalski, 1911) Filchner had influential supporters such as Albrecht Penck, a leading scientist of palaeoglaciation, and his theories built a significant element of the expedition plans. However, Penck and Drygalski were rivals in academic terms. The strong support Filchner had in Penck might have influenced Drygalski's mistrust in this endeavour as well. Drygalski also revealed in this correspondence that he did not trust Filchner and that his plans were not original, and some of the programme are only copies from his own expedition 10 years earlier. He also stated that some of the scientists, as well as Vahsel, had asked him for advice because they trusted him more than Filchner. In this entire correspondence, Drygalski expressed his contempt for and lack of confidence in Filchner. This strengthened Vahsel's position before the ship had even set sail. Nevertheless, who was Richard Vahsel?

Richard Vahsel was a navy officer with Antarctic experience. He was well educated, could move in German society, and knew “the rules of the game”. Besides, Vahsel, being from the navy, had the advantage that the expedition was considered a marine endeavour. Most of the selected officers and scientists supported this view. Filchner was an army officer and, for some time, the rivalry between army and navy had been a striking aspect of the German Empire and its social fabric. Establishing the German Navy was a crucial move in the colonial and imperial rivalry with England. Alfred von Tirpitz's (1849–1930) long-lasting plans for building a strong navy (he was a driving force behind the rise of the German Navy) were widely circulated through the newspapers and other propaganda efforts undertaken to get the wider public behind the project. Also important was that the navy, especially in the upper ranks, was seen as a “safe haven” for the aristocracy and the wealthy upper class. The army, especially the lower ranks, was considered vulnerable to socialism. Back in 1903, on the return of the German National Antarctic Expedition, led by Drygalski, who was a geographer, there was much discussion in newspapers on who should be the leader of an expedition to the south polar regions. Newspapers argued strongly against a non-navy leader stating that an expedition to the south polar regions was too important to let a “geographer, zoologist or geologist” be the leader. The argument was that it was disturbing to put a naval captain under the command of a scientific leader and, in fact, this might even be responsible for the unsuccessful attempt to go further south. A scientist should only be a “passenger”.

But because discovery successes are today particularly in the interest of the research in the South Polar Regions, therefore, first and foremost, the experience, initiative and daring of the navy personnel is to be placed in its service, whereas the pundits can form part of the staff within, where they have plenty of opportunity to achieve something useful. (Argus-Nachrichten-Bureau, 1903)

Vahsel understood that there are more facets in his favour. Years before, Filchner had become popular with his expeditions to Asia, but on his Tibet expedition (1903–1905) he had an associate, Albert Tafel (1876–1935), who accused Filchner of cowardice. Tafel based his assertion on the fact that when a local tribe attacked the expedition, Filchner destroyed parts of the equipment, so they did not fall into the enemies' hands. Tafel disagreed with Filchner's research methods and claimed that he always had to work harder to get his part done. Therefore, he was distraught by the destroyed equipment he needed. In the end, Tafel even accused Filchner of sloppy map making and being a fraud in scientific terms. A series of trials followed which restored Filchner's reputation and his work. It is interesting that some of the same arguments used by Tafel were often applied against Filcher in the preparation phase of the Antarctic expedition to undermine his position as a leader. Vahsel even declared publicly that he would put him in irons if he would not behave on board and he referred to several accounts, which came all from Tafel's previous assertions (Filchner, 1957).

Another argument was that Filchner wanted to profit financially from the expedition. Although he was successful in securing funding for his endeavour, he had no ambitions to enhance his personal finances. He reflected, in a comparatively self-critical manner, on some of the false accusations in his Feststellungen (Kirschmer, 1985; Filchner, 1957), which he wrote at the end of his life. Filchner had been divorced from his wife, which devastated him, and he commented on the reason why he wanted to put this expedition together:

It was very necessary to find a new purpose in my life and it should be demanding so that I could forget for a while [my divorce] and can find myself in it. (Filchner, 1957)

The fact that the expedition should happen at this particular time and his divorce could have encouraged such an accusation. Vahsel was later identified as the initiator of these accusations; in the end he was forced in a sworn statement to stop making further defamatory statements regarding Filchner. The captain from the previous German National Antarctic Expedition, Hans Ruser (1862–1930), warned Filchner of Vahsel and even used the following terms: “Do not trust Vahsel and Lorenzen [first officer]” and further ”Particularly Vahsel is a power-hungry person and a dedicated intriguer.” (Rack, 2010, p. 113)

A more delicate matter was that Tafel accused Filchner and his wife, who accompanied him at the beginning of the expedition in Tibet, of using the accommodation in a monastery as a “toilet”. That was also rebutted in a hearing. However, this story was repeatedly used to undermine Filchner's respectability. It was even a part of a bad practical joke when some of the expedition members put a pile of excreta in front of his cabin door on the way to the Antarctic. Filchner was also bullied by an expedition member recording the amount of time he spent on the toilet. He had experienced a problem with his bowel since his excursion in the Pamir Mountains (1900), where he used a wooden saddle that affected his defaecation. Filchner, naturally greatly embarrassed, did not react to stop these actions.

The expedition was finally underway in August 1911. Filchner had to conclude some final matters in Germany before he joined the expedition in Buenos Aires. He was already on his way when he received word that conflicts had emerged between Captain Vahsel and the interim leader, Heinrich Seelheim (1884–1964). The situation between the two men became so tense that Vahsel wired Filchner an ultimatum that he would leave the expedition if Seelheim kept going on. Filchner was pleased with this decision because he thought he had found a replacement for the current captain in a young navy officer, Alfred Kling (born 1882, no date of death available) (Filchner, 1957). When Filchner arrived in Buenos Aires, Vahsel had changed his mind again and stayed; Seelheim left the expedition of his own free will. Kling became an officer on the Deutschland. Filchner now had one navy officer on his side. In the meantime, the officers, all chosen by Vahsel in the first place, and most of the scientists grouped in opposition to Filchner.

On the way to South Georgia, one of the two physicians, Ludwig Kohl (1884–1969), had an appendectomy. His recovery was slow, so he had to remain in Grytviken. The result was that the second surgeon, Wilhelm von Goeldel (born 1881, no date of death available), was now the ship's physician. He was a great opponent of the expedition leader.

In South Georgia, the expedition members examined the island and prepared themselves for the upcoming journey south. Carl Anton Larsen (1860–1924), the leader of the whaling station in Grytviken, conversed with Vahsel and other expedition members and recognised the factions within the group. However, at this point, it looked promising that the “dust had settled”. At least, the expedition members were still communicating with each other.

At first, the expedition progressed well with excellent scientific results. The interaction on board started to become tense again but was still manageable. However, the captain had a serious medical condition; he was suffering from syphilis. His decision-making has been compromised by the much developed illness, and Vahsel wanted to go back to Grytviken as soon as possible. The plan was to set up a group of scientists to winter over on the ice. Everything seemed to be secure when building the station. However, a king tide turned the iceberg over. Luckily, nobody was killed and most of the material could be saved. From that moment on, the situation spiralled out of control. The question was how that could happen. In the first instance, the Norwegian ice pilot, Paul Bjørvig (1857–1932), was consulted, and the place seemed secure to build the station on it. However, it turned out that Bjørvig never agreed to this place for a landing. The exact course of the event may never be fully reconstructed due to a lack of source material. We rely on Bjørvig's account and Filchner's Feststellungen. The point is that Filchner lost his command of the expedition entirely from that moment on. Bjørvig did not take a position between the captain and the leader, and he was very blunt when he was asked directly. In his meeting with Filchner he pointed out that he had never liked that spot in the first place, but the captain and the scientists (opposition group) wanted that place for the landing. “I asked him [Filchner] who the expedition leader is, he laughed and said, that he is it.” However, that did not convince Bjørvig, and he continued in his account it would be “Filchner's duty to put the station where he wanted it to be and not where the others demanded it”, and he continued that he spoke in blunt terms to Filchner about his leadership:

He [Filchner] did not like what I said, but some of the commanding officers and scientists didn't [like] it either. But I did not care – as long as they recognised that I was right – and that was the main point [about the landing point]. (Rack, 2010, p. 70)

However, Filchner had effectively lost any authority on board he might have had in relationship to Vahsel, and Bjørvig lost all his respect for the officers, scientists and, especially, the expedition leader. Bjørvig, returning after the expedition to Buenos Aires, had to sign a notarial certificate that he was against that landing point and that Vahsel did ignore his judgement and even forced him to keep this a secret in front of Filchner (Rack, 2010, p. 75).

During the austral night, beset by ice, many small incidences culminated in a life-threatening conflict on board the Deutschland. The opposition group formed a strong bond, and Filchner and his followers isolated themselves more and more. Vahsel's illness progressed, and he died in August 1912. Even at this point, the expedition leader had been left out and was informed at a later time about the captain's death and that gave Filchner a lot of room for speculation. He revealed in his Feststellungen that he considered the possibility that Vahsel committed suicide. Officially, Vahsel died from heart and kidney failure. That syphilis was the cause was not mentioned in any official reports.

According to navy regulations, the first officer, Wilhelm Lorenzen (no birth or death dates available), became the new captain. However, Filchner never accepted him in this position, because he hoped his first choice, Kling, would take over. Lorenzen himself was not fit for the job. Even Vahsel mentioned that fact in a conversation with Larsen back in Grytviken. As it turned out, Lorenzen had severe mental issues, which might have been triggered by the chaotic situation on the Deutschland. The situation became so tense that Filchner and Lorenzen only corresponded via an order book and never face to face. In the end, the circumstances became dangerous for Filchner and his few supporters. At the peak of the conflict, some of the Filchner group and he himself slept with loaded guns on the cabin floor, for fear of being shot.

As soon as the ship became free from the ice, they returned to South Georgia. When the ship sailed into the harbour, a tumult broke out on-board. The disappointment in the leader, the aggression between the two groups, and many more underlying conflicts broke loose. Larsen taking control, the situation could be settled for the moment. He talked to all involved and explained to them what the consequences of mutiny were, and everybody should conceal the matter to avoid further conflict and serious damage to their reputations and careers. This resolved matters for a short period, but as soon as the expedition members arrived back home, a series of trials followed.

Filchner was a good researcher, but – unfortunately – a weak leader and the circumstances, which occurred from the start of the endeavour, intensified the problems throughout the whole expedition and beyond. His expedition plan was promising, and he had a distinguished group of scientists around him, but he could not take advantage of the full potential of the mission. He missed opportunities to clearly establish the purpose of the expedition and recognised, too late, that the expedition was changing from a scientific endeavour to a marine one. The choice of the captain, in terms of personality and poor health, was a strategic mistake. That the expedition members could survive in such chaotic circumstances is almost a miracle. Unfortunately, because of the lack of source material it is not possible to explain the survival of the expedition members in more detail and can only be speculated.

The scientists took advantage of Filchner's lack of leadership and focussed on their own work. After the expedition, they published their findings within their own peer groups but dismissed the opportunity to publish an official expedition procedure. They despised Filchner so much that they opposed this approach publicly. This might be the reason that this expedition is often overlooked for its scientific achievements. Filchner had a sort of trauma from his experiences, as seen in the correspondence he had with Vivian Fuchs (1908–1999) in 1956. He advised him strongly to be careful when choosing the captain and keeping the lead from the beginning to avoid disappointments in the end.

Filchner relied too much on the image of himself as a strong man who wanted to bring the German Empire in the ranks of the other great Antarctic nations, like Great Britain. He had exceptionally good references from his military colleagues in commanding troops, but in the Antarctic other skills are more important. The chain of command in the Antarctic is not written in a military handbook that he had with him. Good leadership in the Antarctic is based on the same ambition and target, the consciousness of the hostile environment and mutual respect for each other. Filchner did not recognise that early enough, and his companions did not pay the respect towards him because they did not see him as a leader. The expedition members of the opposition group made that clear in the events in Grytviken on their return from the ice. It is clear that leadership is not guaranteed by a hierarchical position but more by the charismatic ability to lead a group in an exceptional environment. Filchner missed his chance and never could gain the momentum to be the real leader of his own expedition.

Filchner had an eventful and successful life; however, he had an inconsistent character and his opponents on the Antarctic expedition were not easy to lead either. The combination of a strong-minded opposition group and a weak leader, fighting against accusations of all sorts before the expedition started, was a dangerous mixture and a disaster-prone expedition was the result.

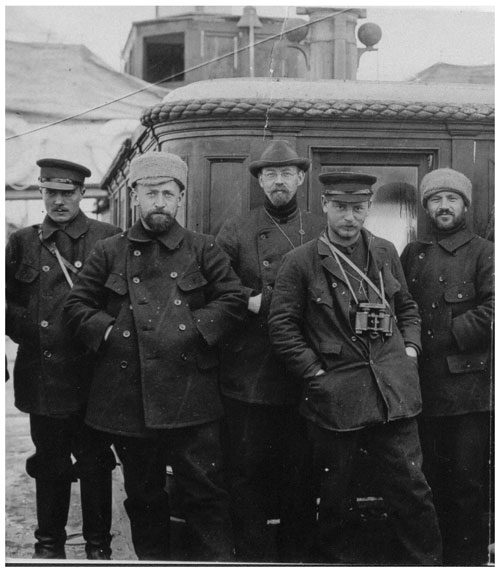

Figure 1Erich Barkow, the expedition's meteorologist (second from the left), with four of his colleagues on the ship Undine (photo taken from Barkow's diary).

To visualise the faction on board the Deutschland and even after the expedition, I found two photos, presented here. Barkow produced a clear copy of his diary and used a photo, showing himself and four of his colleagues on the ship Undine (Fig. 1) (Barkow, year unknown, p. 27). The quality of the photo was very bad and I asked my supervisor, Lars Ulrich Scholl, former director of the German Maritime Museum, Bremerhaven, whether he had a better copy to use in my thesis, and he gave me the photo seen in Fig. 2. It is the same photo as in Fig. 1, but in higher quality, bigger cutout, and signs of manipulation. It shows seven instead of only five persons. Apparently, the left and right margins once were cut off, before taken together again. This treatment removed one person at both margins, respectively, Filchner to the left and Felix König (1880–1945), mountaineer and sled dog handler, on the left-hand side. My interpretation is because Barkow was part of the opposition group he disliked Filchner and König so much that he did not want to have them in his clear diary copy. The photo was restored later, and one can clearly recognise the cutting at a closer look (Fig. 2).

Figure 2Same group as in Fig. 1 in a restored photograph. In addition to the five people shown in Fig. 1, Filchner appears to the right and König to the left, both of whom were cut out of the photo Barkow used for his diary, shown in Fig. 1 (Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum, Bremerhaven, no catalogue number available).

However, Filchner succeeded in many subsequent expeditions to Tibet and Nepal, but he never led an expedition again with more than a handful of members. Most of the time he was a loner, but in his research he was successful and respected.

The Filchner diaries and Feststellungen are in the Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; see reference list.

The translated Bjørvig diaries are in the archives of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Science. The originals are in the Norwegian Polar Institute Library, Tromsø, Norway; see reference list.

The letters from Drygalski to Hofrat Wagner are in the archive of the Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen; see reference list.

Because this is a history article in which mainly archival material was used, the usual dataset depositories are not available like in the hard sciences. I have indicated the accessibility in the references.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

I want to thank the journal Polarforschung for the opportunity to publish this article in English, attracting a wider readership. Thank you also to the reviewer for the constructive comments on the manuscript.

This paper was edited by Bernhard Diekmann.

Argus-Nachrichten-Bureau: 3. Dezember 1903, Institut für Länderkunde, Kasten 90/5, 1903.

Barkow, E.: Tagebuch des Meteorologen Erich Barkow an Bord der Deutschand 1911–1912 (handwritten, no year available, in private hands).

Bjørvig, P.: Schilderung einer Reise in die Weddell-See mit der Fichnerschen Expedition 1911/13, [original: Oblevelser i Nord of Sydishavet ob Paul Bjørvig 1871–1911, NPOLAR Dagbøker, Norwegian Polar Institute Library, Tromsø DAG-008] translated into German by Dörte Burhop, Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung, AdP, NL 15, Akz. 2014/040 (AdP: Archiv der deutschen Polarforschung, NL: Nachlass, Akz: Akzession).

Filchner, W.: Festellungen. Bericht über die Deutsche Antarktische Expedition (1956–1957), Filchner-Archiv der Bayerischen Akadamie der Wissenschaften, Gruppe I-b, 4a1 (typed manuscript), 1957.

Kirschmer, G.: Dokumentation über den Verlauf der Expedition 1911–12. München 1985, Filchner-Archive of the Bavarian Academy of Science, Group 1-b, 4a1 (typed manuscript), 1985.

Krause, R.: Zum hundertjährigen Jubiläum der Deutschen Antarktischen Expedition unter der Leitung von Wilhelm Filchner, 1911–1912, Polarforschung 81, 103–126, http://hdl.handle.net/10013/epic.40201.d001, 2012.

Rack, U.: Sozialhistorische Studie zur Polarforschung anhand von deutschen und österreich-ungarischen Polarexpeditionen zwischen 1868–1939, Berichte zur Polarforschung, 618/2010, Bremerhaven, 65–67, https://doi.org/10.2312/BzPM_0618_2010, 2010.

von Drygalski, E.: Letter from Drygalski to Hofrat Wagner, 16 June 1911, Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Sign. Code M. H. Wagner 17, 1911.

- Abstract

- Kurzfassung

- Introduction

- Filchner's authority is weakened long before the expedition leaves Bremerhaven

- On the way to the Antarctic

- An iceberg upends, an ill captain and other problems

- The end of a solid expedition plan and its aftermath

- Final thoughts

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Kurzfassung

- Introduction

- Filchner's authority is weakened long before the expedition leaves Bremerhaven

- On the way to the Antarctic

- An iceberg upends, an ill captain and other problems

- The end of a solid expedition plan and its aftermath

- Final thoughts

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References